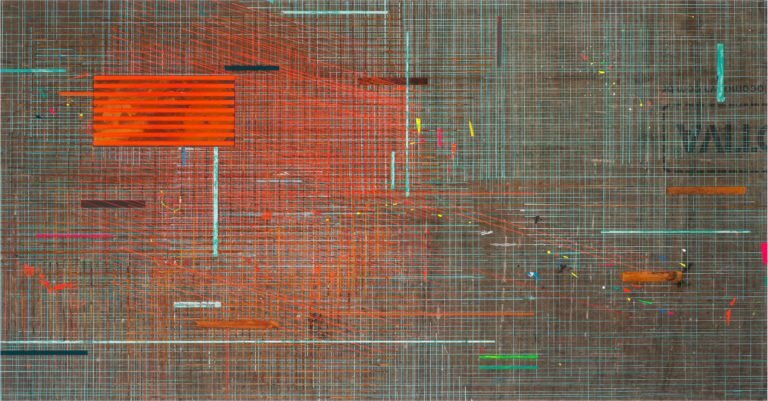

Many times, abstract art is the result of examining something tangible or conceptual, taking it apart, and presenting it in a different manner. Brazilian painter and sculpture artist José Bechara understands how to take complex, external influences from one’s life and transform them into meticulous creations that cause us to question the depth of what they may be representing. He touches on how his work engages with the space where they’re found. “Through the experimentation of different materials and territories in dimensional and three dimensional works. Along the years, I have always worked on paintings, sculptures and installations dialoguing with the space (by building or activating it), memories and time, as well as its impacts on individuals and society,” he says.

Aesthetic

Each of Bechara’s pieces are creatively planned out. The sharp edges, raw materials, geometrical conjunctions, and linear pathways show flexibility within a rigid setting. Each piece takes on such a dimensional stance that it allows viewers to contemplate its many layers and angles, even in the paintings, where the thin lines are delicate mazes that blend with the industrial-like backbone found in the background.

He explains, “Even as a fan of geometry, I like to confront its history and tradition, rejecting the idea of a “perfect form” promised by geometry as we see in art history. Geometry, in my work, celebrates failure, doubt and it hesitates against life, as I believe we do, as humans, every day.” The sculptures instigate a gravitational challenge for our perception of what we already know about art to expand. Many of these pieces act like a rebellion against what shapes should look when combined. They force you to embrace that imperfect perfection, chaos, and closely inspect each linear and material interaction within each piece.

Deeper Meaning

It is the raw elements found in Bechara’s work that makes the pieces even more engaging. The use of oxidation, wood, and subtleties of color allow the sculptures and paintings to hold a level of fragility. There’s a sense of impermanence too, as if everything could change with one touch. One that is tied to deconstructive elements of what is underneath, like looking at the structural bones of a home instead of the facade.

This narrative takes us back to the original stance of personal dialogue with the external world when looking at his work. One that speaks of looking within to discover what is underneath the surface, and then rebuilding that narrative based on what you find there, first and foremost. Bechara expands on this topic, “I am not a narrator of daily life; I am an abstract artist. However, I am always attentive to the average dramas of existence, especially of the effects social dynamics have in individuals' lives. The relationship between past and present, work and environment. In a certain way, I believe some of my main questions, described above as failure, inexorability of time, finitude, hesitation and the fragility of daily life, touch on some people’s social dramas.”

Conclusion

The way we look at Bechara’s work can provide insight on our lives’ own twists and turns. At times, things fall apart, literally or figuratively, and that is what his work is asking us to look at sometimes. That necessary curve ball that life throws at us is at times a necessity to regain perspective and rebuild in a different, better way.

All photos courtesy of José Bechara. For more about his work, please visit his website.

Today’s poem represents the multidimensional aspects of life found in José’s work:

BY JOY HARJO

My house is the red earth; it could be the center of the world. I’ve heard New York, Paris, or Tokyo called the center of the world, but I say it is magnificently humble. You could drive by and miss it. Radio waves can obscure it. Words cannot construct it, for there are some sounds left to sacred wordless form. For instance, that fool crow, picking through trash near the corral, understands the center of the world as greasy strips of fat. Just ask him. He doesn’t have to say that the earth has turned scarlet through fierce belief, after centuries of heartbreak and laughter—he perches on the blue bowl of the sky, and laughs.