When artists collaborate, it is like a world of creative possibilities. But what is a remarkable task in this process is the ability to work well together while developing ideas that will spark something new individually, and then collectively. For artists Nikki Brugnoli and Anne C. Smith, this task has become part of their professional lives, and though each artist individually showcases work, when the two collaborate, it becomes second nature to their overall process.

Brugnoli remarks on the close relationship the two of them share:

“It has always been a part of the widening conversations about our practices, our lives, our families, and our friendship - to connect in this way. [The past] 10 years have been fruitful and we've evolved from initially an academic mentorship to be very close friends; sisters,” she says.

The two first met at George Mason University in 2012, when Smith was a graduate student in the MFA program and Brugnoli was teaching and advising. Over time, they developed a bond discussing art, poetry, motherhood, and academia. They formed a deep friendship that would eventually evolve into that of collaborative creators.

Inspired Thoughts

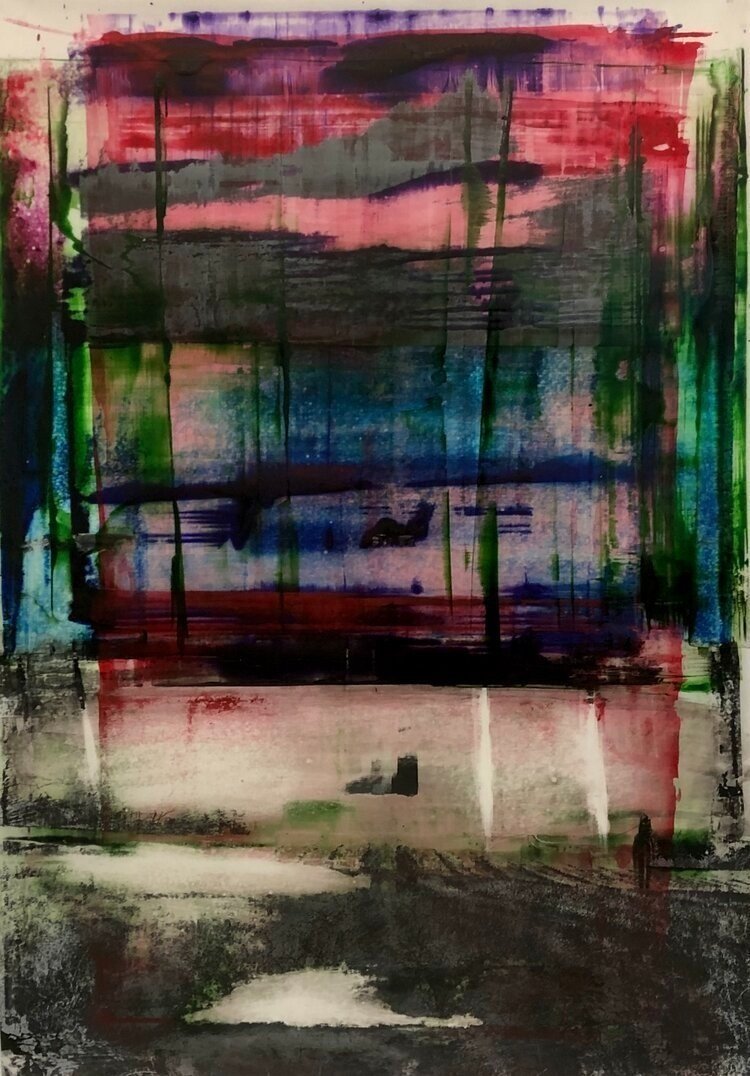

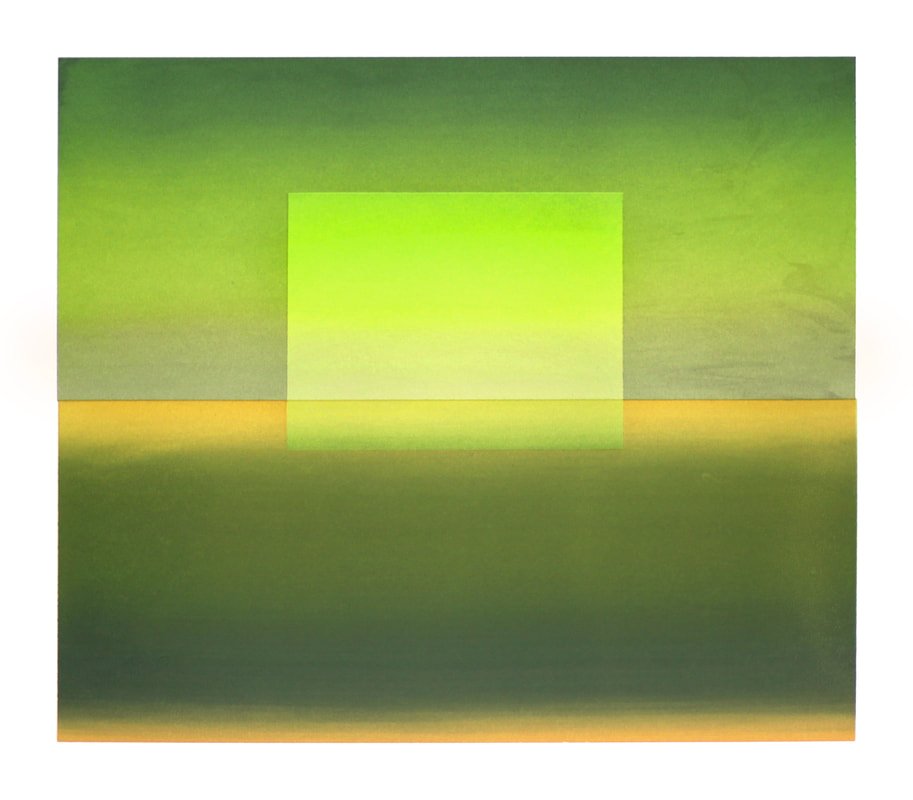

Nikki Brugnoli, Horizon Lost, 2020.

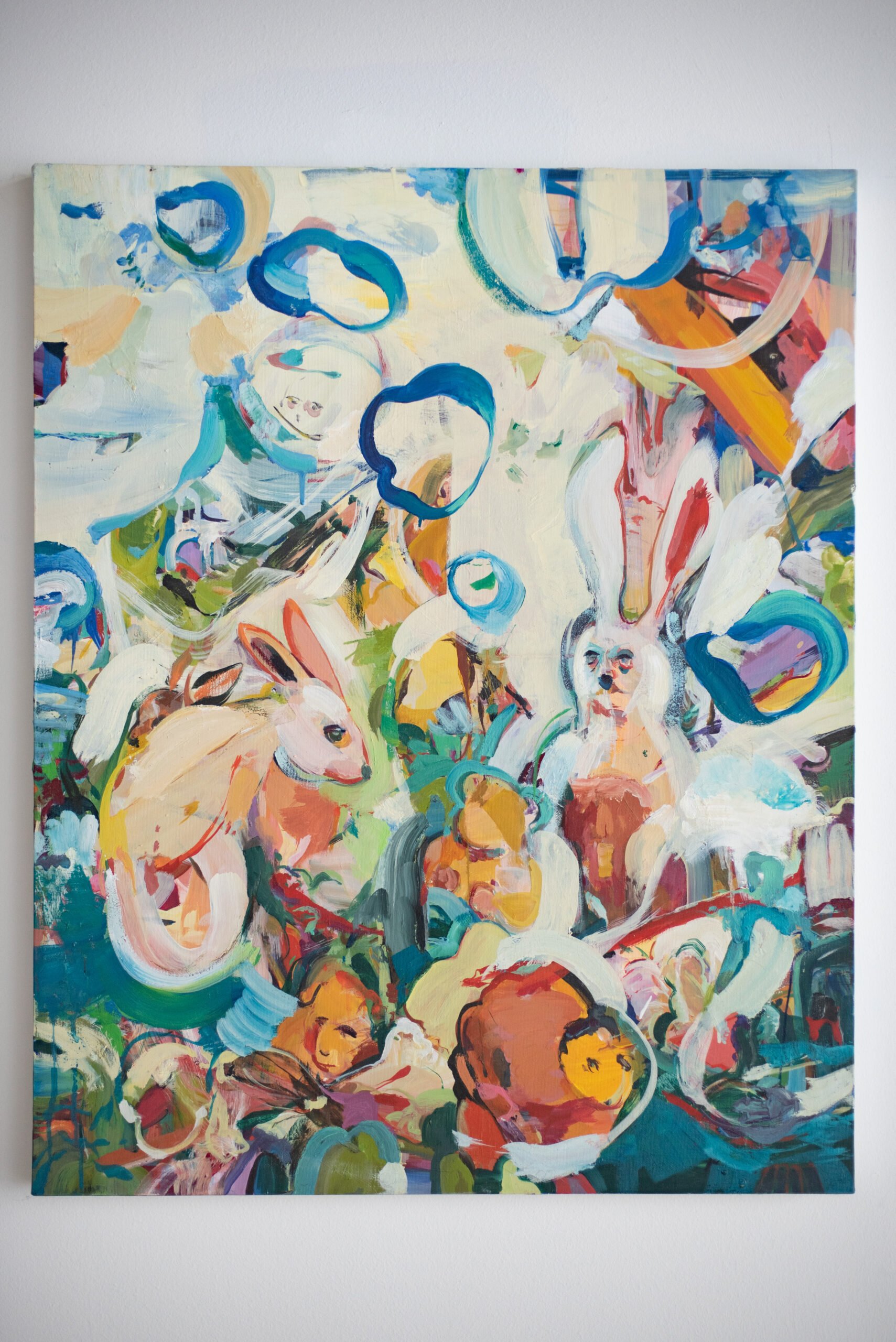

When you look at Brugnoli and Smith’s works, you can’t help to notice the differences in their styles. Brugnoli works with screen printing, layers, mylar, and figurative aesthetics to her imagery, while Smith’s work tends to be more abstract in context. Both artists merge well from their distinct perspectives thanks to their deeper understanding of their inner visions and each other. They both produce beautiful work that converges to show similarities in subtle ways but still remains solely that one artist’s voice.

Brugnoli’s work touches on metaphorical layers of depth, as one finds when viewing it, it is like uncovering pages upon pages of a bigger work, and when you find the gist, it is even more perplexing. As for Smith, her work is highly detailed as she plays with scale and ensures you take your time with every part of her art pieces; a fascinating way to appreciate the work itself. Both artists have a strong approach to their work, and it is that intentionality in technique and detail that allows for a beautiful coexistence when presenting their work together.

Brugnoli speaks on how important it is for her and Smith to get in touch with the physical aspects of their practices, and how this serves a greater purpose. “I think what stands out for us the most is our approach to materials. We are both very physical "makers" and we like drawing, as a practice, but also discuss drawing as a metaphor to larger ideas about our lives - like memory and ritual,” she says.

The differences in aesthetics between the two artists allow each to voice their opinions, consider new viewpoints and possibly take those in and implement them. They see this practice as essential to their collaboration style, which is open and communicative, and in turn, allows them to broaden their perspective, technique, and process.

Smith remarks on this experience, “Nikki always asked questions that took me aback because they were so direct and challenging! I really valued that, and our conversations helped sharpen my focus in the studio. I was also inspired by Nikki's resourcefulness and that she provided a sort of model for incorporating family and studio practice.”

Process Matters

Anne C. Smith, Sift, 2018. Artwork from the Forces Fleeting exhibit.

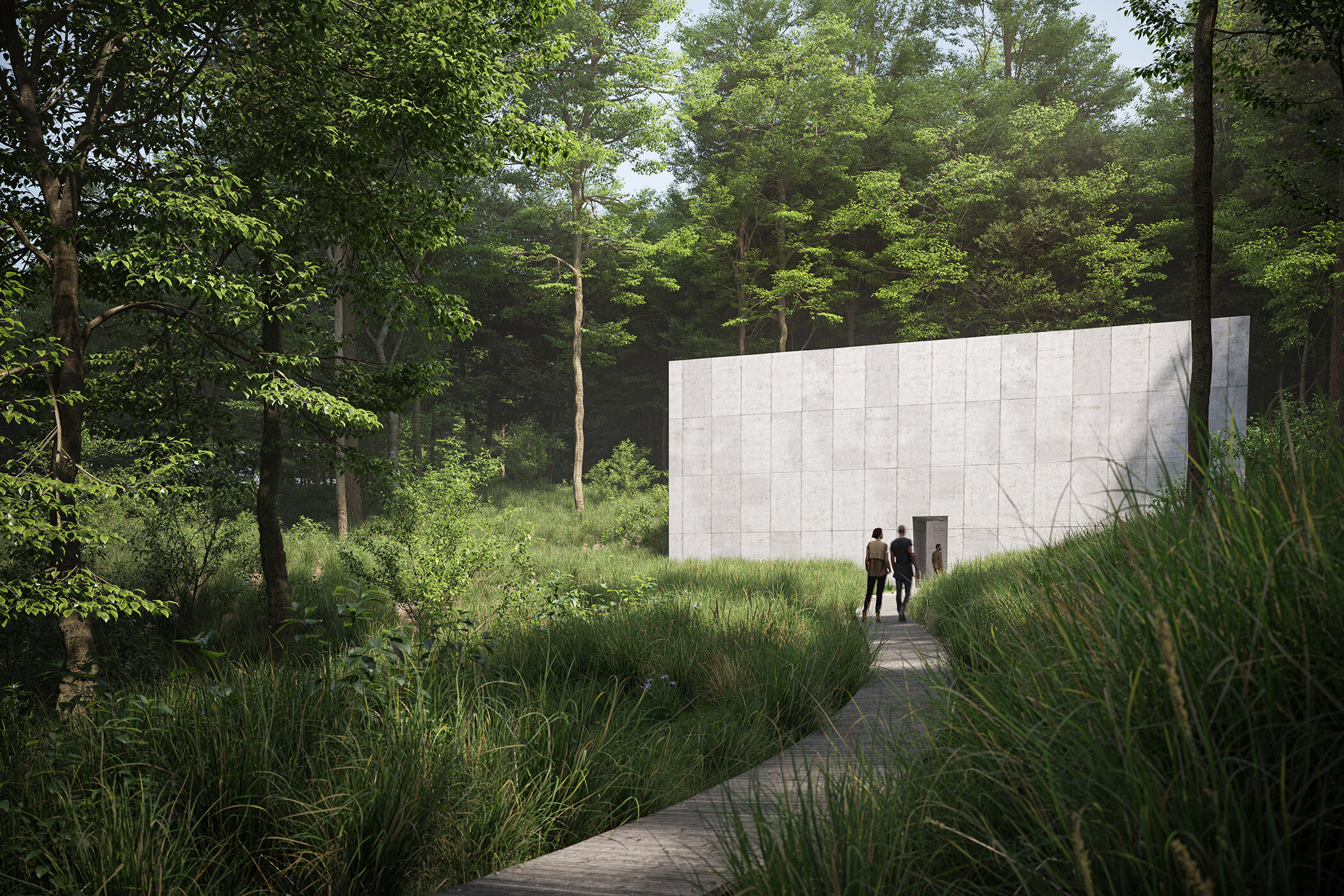

The behind-the-scenes collaboration between Brugnoli and Smith is what makes their work even more compelling. It takes time, effort, and communication to be able to work well with someone, but that’s not all. There also needs to be a sense of understanding of one another’s styles and a support system that holds space for creative freedom, where both artists feel comfortable creating and being expressive. In Forces Fleeting, their recent exhibit at the Athenaeum Gallery in Old Town Alexandria, Brugnoli and Smith both showcased dark color pieces that were contrasted by the materials each artist used, with Brugnoli using mylar, and Smith using ink-stained linen. Both sets of works allowed for the artistic elements in every piece to show the artist’s style and skillful technique in her own way.

For Brugnoli, the creative process can be transformative and helpful in accomplishing goals:

My practice is geared more toward process - a very clear process of incubation, ideation, and transformation that tends to be very immediate and intense. I tend to procrastinate and wait until only a small window of time remains to actually do the physical work, while months and months, even years, can go into the preparation and writing.

Anne and I decided in the beginning that we would document, via text message, email, etc our emerging conversations, specifically about Forces Fleeting, and use that as a springboard. All of the planning was very intentional. I think we both benefit from clear deadlines and the high expectations we have for one another to create our best and strongest work. There was never any question that the outcome of Forces Fleeting would only deepen our respect for one another as artists and friends.

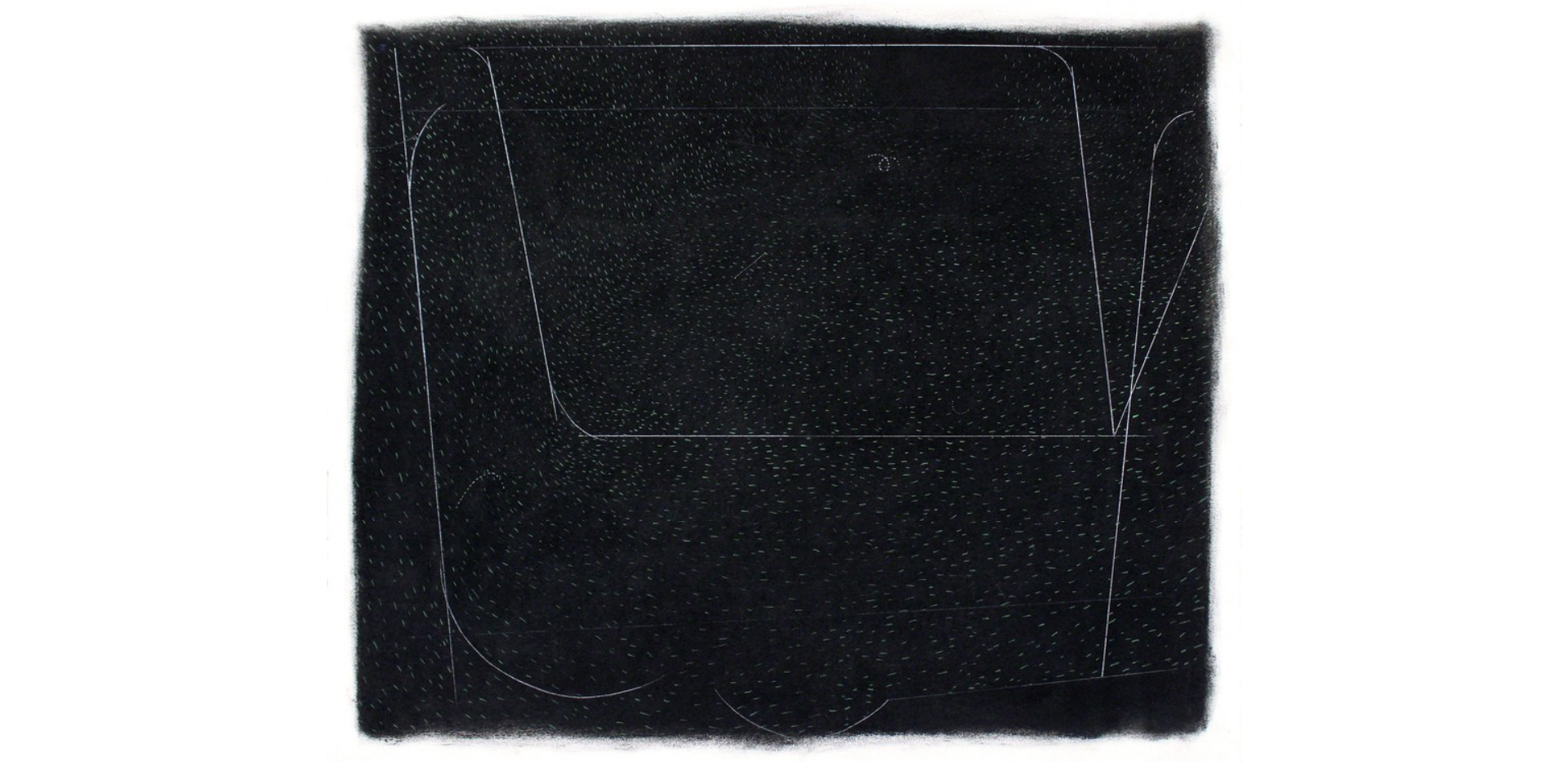

Nikki Brugnoli, Copper and Gold, 2021. Artwork from the Forces Fleeting exhibit.

In Forces Fleeting, both artists played into their differences and bond at the same time. They intermixed their personal process and individual experiences into an expanding universe, where their work created insight into one another in its own way. Brugnoli touched on thoughts of personal moments, time, and loss, in her layered technique, where dark and shimmering shades complemented her screenprinting. While Smith allowed for specific places and spaces to serve as a platform for her stance on how we live our lives as we move, drive, and explore from one place to another, and how all this adds to one individual, complex experience.

Smith remarks on this:

In our work, we've found connections between what we think about: landscape, place, and home. And also in our practices that fuel: walking, silkscreening, and drawing, for example. We've wanted to collaborate on a show for a long time, and we finally get to do that with this show, Forces Fleeting, at the Athenaeum. The work in that show touches on those overlapping themes, each with our own perspective and experience brought to the work. We're both working mostly monochromatically in these pieces, with areas of deep, dense black ink -- I think we both find poetry in those shadowed areas. By showing together, our work can have some of those conversations visually that Nikki and I have had in the studio over the years.

Concluding Musings

Anne C. Smith, Point of Longing, 2020.

Successful collaboration is a fascinating thing, and in art even more so. What we see in Brugnoli and Smith’s work is the interconnectedness of two distinct forces in the art field that allow for growth and support in one another’s voices, own challenges, and sense of direction.

Brugnoli points out, “For me, what reveals the strength of a successful collaboration is the shape of trust exchanged and created between two makers.” It’s true that this aspect can really build on the momentum of making things happen in a positive direction, and these two artists know exactly how to make that dynamic work for their individual and collective styles.

For Smith, there is an added intuitive exercise that allows for the creative success of their work together. She says, “There's a shared goal of wanting to see the other person realize their most gut-felt vision in a way that sings. With that kind of foundation, the outcome of the work grows naturally into something we're both proud of.”

Collaborative creativity can only flourish in places where it’s fostered. These places are found where even a challenge is seen as an opportunity to learn more about the process and how to better create together. That level of understanding is what Brugnoli and Smith share, and that synchronicity allows for a successful collaboration that can stand the test of time.

Today’s poem reflects on the blossoming collaboration between these two artists:

FROM THE SUN AND HER FLOWERS BY RUPI KAUR

it isn’t blood that makes you my sister

it’s how you understand my heart

as though you carry it

in your body